Hi,

Please take a peek at the following references, if you haven’t already,

Structures or Why Things Don’t Fall Down, J. E. Gordon, (1978) ISBN 0-14-02-1961-7

The New Science of Strong Materials or Why You Don’t Fall Through the Floor, J. E. Gordon, (1976, 2nd ed.) ISBN 0-14-02-0920-4

On that note, though my question (below) may appear to be an attempt to highjack the thread, it’s actual intent is just to back it up a bit.

The following eventually leads to a way of estimating breaking strain. Some preliminaries are required, if only to make sure we are speaking the same language.

Preliminaries

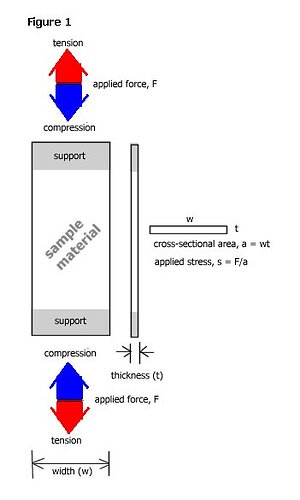

First some definitions: stress (s) is force per unit surface area, and will have the same units as pressure; strain (e) is the ratio of change in length to original length, and has no units, its a pure fraction. For many materials, least when the strain is small (somewhere around 1%, usually less, but sometimes a little more) the ratio of s/e (stress to strain) is constant and is called Young’s modulus –i.e. s/e = Y. Young’s modulus is also known as the modulus of elasticity, and possibly by a few other names too.

Young’s modulus is not a bad indicator of ‘stiffness’ when used correctly, but ‘stiffness’ as it is commonly used, often involves both Young’s modulus and geometry. The reason being that it is often used in reference to force rather than stress, e.g. the restoring force of a spring or wire is classically given by F = -kx, where x is the extension of the spring and k is the stiffness constant. I’ve mentioned this with the hopes of avoiding confusion.

The ultimate tensile strength (UTS) of a material is that minimal stress at which the material will fail. It is important to understand that here the reference is to a material, not a structure. Obviously, when testing materials it is impossible to not consider structure, it’s just that the protocols for testing have standardized structure so that to the extent possible, structure as a factor is eliminated. Therefore UTS is a best estimate (given the constraints) for the stress at which a material will fail.

This next statement will likely cause some controversy. When considering a composite, like fiberglass/resin, the resin plays a very little role with regards to strength –i.e. virtually all of the strength comes from the fiber, and for fiberglass composites that’s glass.

Before continuing, an additional note on terminology; strength is one thing, toughness is another. You can have a very strong material, but a brittle one, and therefore somewhat useless for certain applications. Toughness is what makes composites unique and valuable – i.e. their ability to handle cracks or fractures without totally failing. Perhaps this thread may migrate towards a discussion of toughness strategies, but right now it seems to be about strength. The point being that toughness and strength are two different engineering concepts and confusing them can get you in trouble.

Glass

The Young’s modulus of glass is something around 60 GN/mm (that’s 60 giga-newton per meter-squared). The ultimate tensile strength of glass is around 1 GN/mm (that’s 1 giga-newton per meter-squared). This puts a UTS-strain at e = s/Y, e = 1/60 = 0.017 ~ 0.02 or 2%.

Recalling that e is the ratio of change in length to original length, then if the longitudinal bottom length of a surfboard is L, it would have to suffer a change of eL in length before some of the glass fibers might start to fracture –i.e. e = (change in length)/L, then (change in length) = eL.

The Question

Here’s my question, what’s the bottom length of your surfboard and what’s its wide point width? Using the above crude calculation to estimate the required changes in length or width before fracture, how often are such changes in length observed?

The geometry of the board will come into play, but assume the simplest case. Also, its assumed that when using the composite the weave is aligned such that it is roughly perpendicular and parallel to the stringer or centerline of the board.

Loaded?

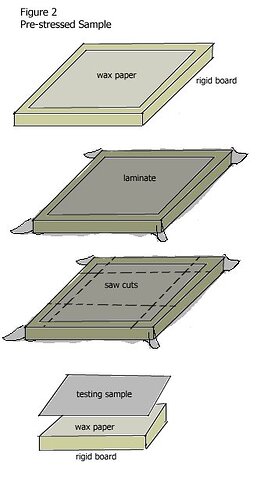

The question isn’t loaded, but there are other issues which have to be factored in. One in particular is pre-stressing. For some composites, like fiberglass/resin the volume shrinkage upon curing can be up to 7%, which sort of translates into a lengthwise shrinkage of up to 2%. This isn’t purely tensile, but it is likely to pre-stress the lamination. Perhaps the thread may wander around to addressing pre-stressing, but right now it seems to be about strength.

Strength has its benefits, but it has it also has its costs. The question, at least for me is, given the application, what is the appropriate level of strength required. Or more precisely, what is the appropriate mix of strength and toughness.

kc